The world is losing forests faster than it can protect them, yet COP30 may be our last best chance to reverse the trend. Since the adoption of the Paris Agreement at COP21 in 2015, forest conservation has become a cornerstone of global climate mitigation and adaptation strategies. Forests not only act as carbon sinks but also support biodiversity, regulate hydrological cycles, and sustain livelihoods, particularly in developing regions. As COP30 convenes in Belém, Brazil — a symbolic location at the heart of the Amazon — this essay critically examines the trajectory of forest conservation over the past decade. It assesses policy milestones, climate finance mechanisms, and implementation challenges, with particular attention to Africa and Nigeria. Drawing upon peer-reviewed literature, multilateral frameworks, and recent policy analyses, including the International Institute for Sustainable Development’s (IISD) explainer on climate adaptation at COP30, this review offers strategic insights to guide decision-making in forest governance.

Progress Since COP21: Policy and Finance

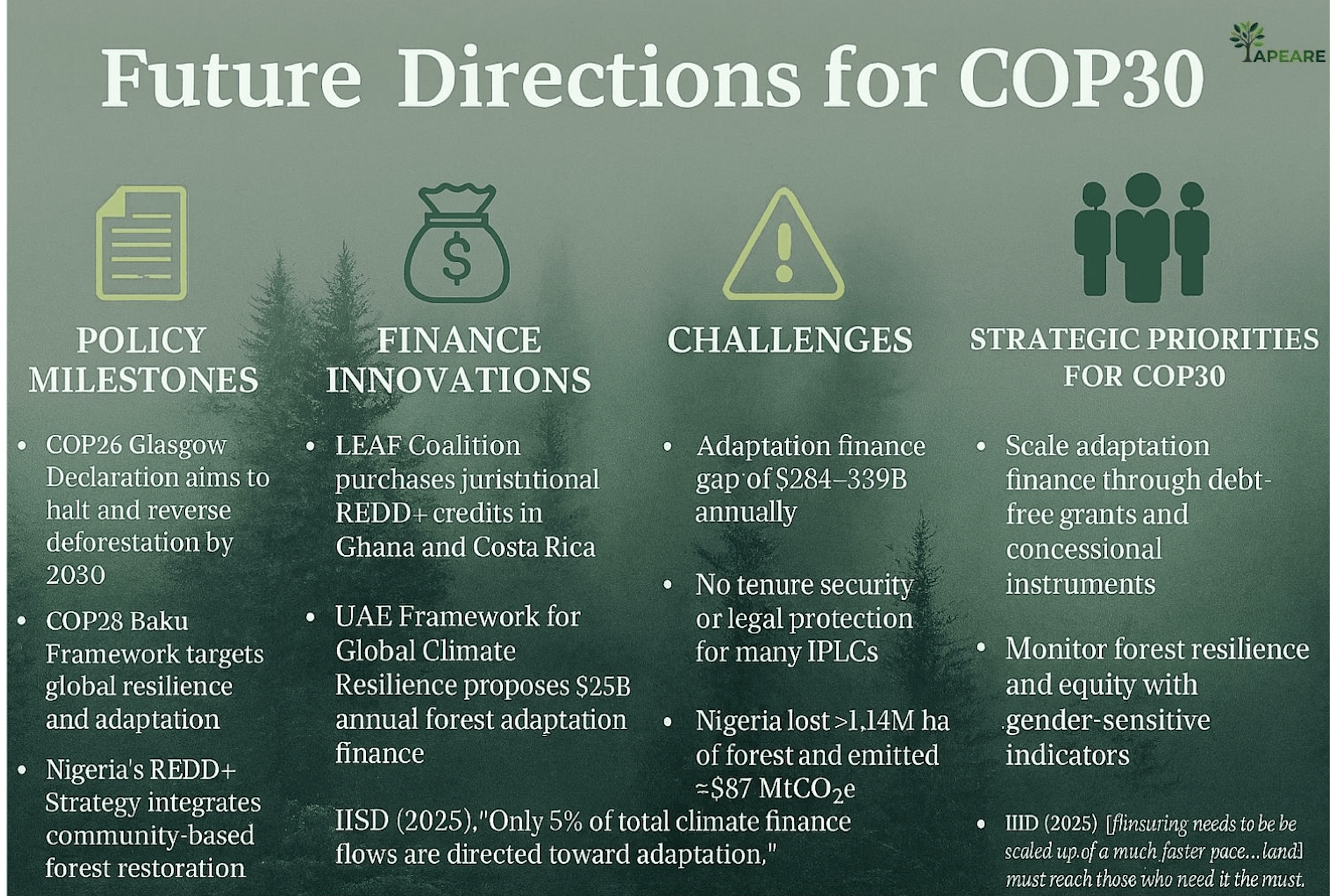

The Paris Agreement’s Article 5 formally recognized the critical role of forests in climate mitigation, sparking a surge of policy commitments. Initiatives such as the Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration on Forests and Land Use (COP26) and the UAE Framework for Global Climate Resilience (COP28) have established ambitious goals to halt deforestation and enhance adaptation efforts (Zhou et al., 2024). Financial mechanisms like the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF) and the LEAF Coalition have mobilized billions in results-based payments, with countries such as Costa Rica and Ghana leading the way in pioneering jurisdictional REDD+ credits (World Bank, 2024).

Despite the increasing urgency of climate adaptation, it remains critically underfunded. The UN Environment Programme’s Adaptation Gap Report (2025) estimates that developing countries face an annual shortfall of USD 284–339 billion. Alarmingly, only 5% of total climate finance flows are allocated to adaptation efforts. As highlighted by the IISD in 2025, “financing needs to be scaled up at a much faster pace… and must reach those who need it the most, particularly the least developed countries and Small Island Developing States.”

Africa and Nigeria: Regional Implications

Africa accounts for over 17% of the world’s forests, yet the continent faces significant climate vulnerabilities. Nigeria, in particular, has experienced alarming deforestation driven by agricultural expansion, fuelwood harvesting, and urbanization. From 2001 to 2021, Nigeria lost more than 1.14 million hectares of tree cover, resulting in approximately 587 MtCO₂e in emissions (Global Forest Watch, 2022).

Forest conservation initiatives in Nigeria, such as the National REDD+ Strategy and community-driven reforestation projects, align with COP30’s emphasis on locally led adaptation efforts. Organizations like APEARE have demonstrated scalable models by integrating agroecology, stakeholder engagement, and GIS-based monitoring. These initiatives resonate with the IISD’s call for “gender-responsive, locally led adaptation that yields measurable, sustained impacts” (IISD, 2025).

However, challenges remain. Issues such as land tenure insecurity, limited access to financing, and weak institutional coordination hinder effective implementation. The IISD emphasizes that “all the finance, indicators, and frameworks discussed at the international level matter only if they are implemented at the national and subnational levels” (IISD, 2025). For Nigeria to succeed, it must fortify its National Adaptation Plan (NAP) processes, integrate forest governance, and ensure that adaptation finance is effectively channeled.

Future Directions for COP30

To ensure meaningful progress in forest conservation, COP30 must articulate a coherent, actionable roadmap that encompasses climate finance, policy integration, and monitoring mechanisms. Central to this agenda is the urgent need to scale adaptation finance through grants and concessional instruments, thereby mitigating the risk of exacerbating sovereign debt burdens in vulnerable economies (IISD, 2025). Equally critical is the development of robust, context-sensitive indicators that capture forest resilience and equity outcomes, with particular attention to gender-disaggregated data and social inclusion metrics.

Policy coherence remains a foundational challenge; thus, forest governance must be systematically aligned with agricultural, trade, and rural development policies to foster synergistic outcomes across sectors. Moreover, empowering Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities (IPLCs) through direct financial support and participatory decision-making is essential to ensuring legitimacy, effectiveness, and long-term stewardship of forest landscapes.

For Nigeria and the broader African continent, COP30 presents a strategic inflection point to reposition forest conservation as both a climate imperative and a development priority. By leveraging global frameworks—such as the Forest Finance Roadmap and REDD+ mechanisms—alongside locally grounded innovations in agroecology, land restoration, and community engagement, African nations can advance inclusive, resilient, and sustainable forest governance.

References

IISD. (2025). What’s at Stake for Climate Change Adaptation at COP 30? International Institute for Sustainable Development. Retrieved from https://www.iisd.org/articles/explainer/climate-change-adaptation-cop-30

UN Environment Programme. (2025). Adaptation Gap Report 2025. Nairobi: UNEP.

https://www.unep.org/resources/adaptation-gap-report-2025

Vizzuality, “Nigeria Deforestation Rates & Statistics | GFW,” n.d., https://www.globalforestwatch.org/dashboards/country/NGA/.

World Bank. (2024). Forest Carbon Partnership Facility Evaluation. Washington, DC: World Bank Group.

Zhou, Kai, David Midkiff, Runsheng Yin, and Han Zhang. “Carbon Finance and Funding for Forest Sector Climate Solutions: A Review and Synthesis of the Principles, Policies, and Practices.” Frontiers in Environmental Science 12 (April 10, 2024). https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2024.1309885.